How Cross-Chain Bridges Work, Where They Break, and What Real-World Systems Should Do About It

Interoperability is the infrastructure problem at the heart of Web3’s next decade. If you think of blockchains as sovereign digital city-states, bridges are the roads, ferries, and air corridors that let goods, money, and information move between them. But those roads are also where value concentrates and where failure turns discreet losses into systemic shocks.

This article explains, with operational clarity and technical depth, how bridges actually function, the subtle failure modes engineers and treasurers must design for, and pragmatic strategies teams can use to minimize risk while unlocking multi-chain liquidity.

A more precise mental model: bridges are distributed state synchronizers

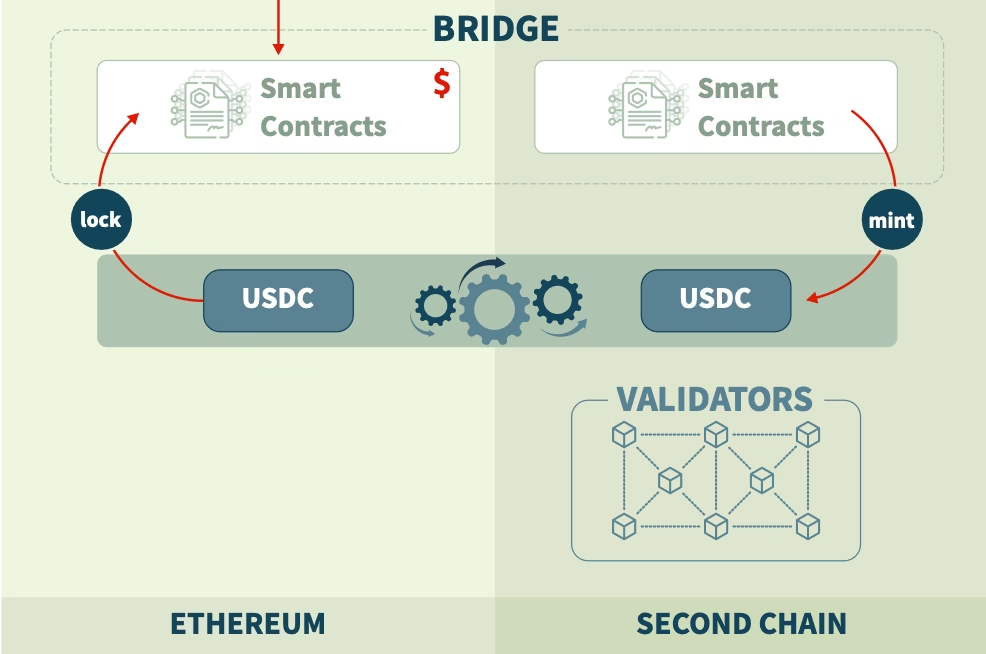

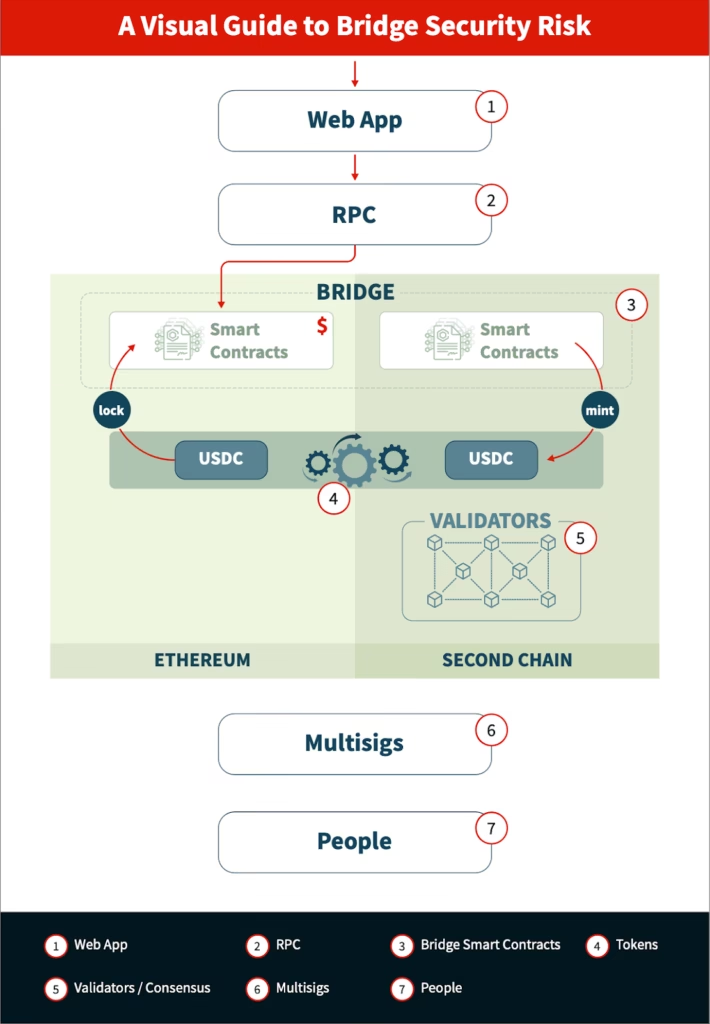

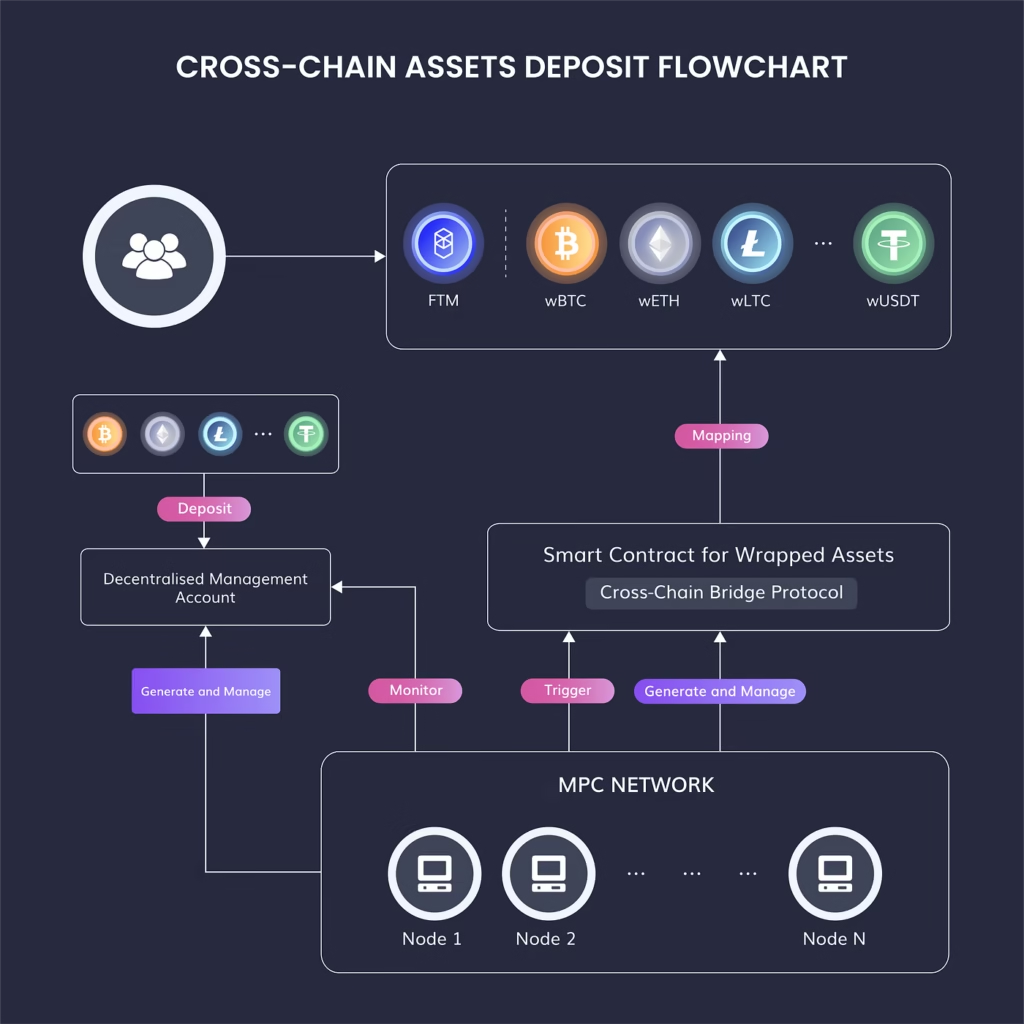

Most summaries say “lock on A, mint on B.” That’s a simplification. Build a more useful mental model: a bridge is a distributed state synchronizer that tries to make two separate ledgers agree about a specific economic fact (e.g., “Alice locked 10 ETH at tx X on chain A”). Every design answers the single question: who, and how, attests to that fact on the destination chain?

Three distinct components typically implement that answer:

- Observation layer– nodes/relayers/light clients that detect events on chain A.

- Verification layer– logic that proves/validates the event (Merkle proofs, SPV-like receipts, zk-proofs, or validator signatures).

- Execution layer– the smart contracts on chain B that mint/burn, release funds, or execute the requested cross-chain action.

Different architectures change which component is centralized vs. distributed, and where trust is concentrated.

Four canonical bridge architectures and their tradeoffs

1) Custodial / Federated (Multisig)

Fast, UX-friendly, but centralized. A known operator or federation holds the underlying asset; the destination chain trusts their collective signature.

Tradeoffs: low latency, high operational risk (key compromise, governance capture). Good for regulated rails where legal recourse exists, poor for trustless promises.

2) Relayer + Light Client

Relayers push proofs; smart contracts on the destination chain run a light client that validates headers or Merkle proofs.

Tradeoffs: strong cryptographic guarantees, but costs and complexity spike (on-chain verification is expensive). Finality depends on the origin chain’s security model and the frequency of relayer activity.

3) Fraud-proof / Optimistic approach

The bridge posts a summary and assumes validity; a dispute window allows challengers to submit fraud proofs.

Tradeoffs: cheaper optimistic throughput, but slower safe withdrawals (challenge windows) and the risk of poorly incentivized watchers.

4) Zero-knowledge (zk) proofs & native message passing

The origin computes a succinct proof that state transitions are valid; the destination verifies the proof instantly. This is the strongest cryptographic guarantee with near-instant finality when implemented well.

Tradeoffs: constructing zk proofs for general execution is hard and resource-intensive; proving full EVM semantics is still evolving.

Common, subtle failure modes engineers under-estimate

These are the modes that bite production systems:

- Reorg and reappearance: origin chain reorgs can invalidate an observed event. Solutions: require multiple confirmations, use canonical finality signals, or light-client checkpointing.

- Sequencer censorship / stuck relayer: if an operator stops pushing updates, wrapped assets become illiquid. Mitigation: multiple independent relayers, fallback dispute primitives, and financial slashing incentives.

- Validator collusion (multisig compromise): federated signatures get stolen or coerced. Mitigation: hardware security modules (HSMs), geographically distributed keyholders, legal wrappers, and insurance.

- Replay and signature reuse: incorrect signature schemes permit the same proof to be used multiple times. Mitigation: include chain-specific domain separation, nonces, and explicit burn/lock receipts.

- Oracle & data-attestation risk: bridges that rely on oracles for off-chain attestation inherit oracle failure modes, build multi-source attestation and on-chain challengeability.

- Liquidity blackholes: wrapped assets accumulate on the target chain but exit is blocked by broken bridge logic; users lose optionality. Mitigation: circuit-breakers, withdrawal limits, and robust monitoring.

Attack economics, not just “can they hack it?” but “is it worth it?”

Attackers don’t just look for bugs; they calculate bounty vs. effort and traceability. Large pools of bridged liquidity are high-value and therefore attract sophisticated, often state-level adversaries. Two design principles follow:

- Reduce single-point-of-failure value concentration. Don’t pool everything behind one multisig or contract. Use segmented vaults with separate guards and rolling limits.

- Raise cost of attack faster than reward. Layer MPC (threshold signatures), HSM, and formal verification with bug-bounties to make exploitation expensive and detectable.

Investors and treasurers should always model bridge risk as expected loss = probability of exploit × loss magnitude, then insure or hedge accordingly.

Practical patterns that work in production

If you run a treasury, exchange, or protocol, adopt layered defenses:

- Multi-rail custody: keep a portion of funds on native chains, another portion in highly secure cold custody, and only minimal working capital bridged for opportunistic yield.

- Incremental bridging: perform small, repeated transfers with monitoring and automated rollback if anomalies appear.

- Multi-relayer redundancy: use a diverse set of relayers and watchtowers; have an on-chain fallback for proof submission.

- Economic circuit breakers: automatic withdrawal halts if unusual patterns (sudden outflows, high slippage) exceed thresholds.

- Formal verification + annual pentests: code audits are table stakes; formal proofs for consensus-critical components are strongly recommended.

- Insurance & reinsurance: buy cover from on-chain insurance protocols and traditional insurers where possible; consider captive insurance via DAO treasuries.

Cross-Chain Messaging vs. Asset Bridging

There’s a huge shift from “moving tokens” to “moving intent.” When a contract on chain A can trigger deterministic logic on chain B (with verifiable guarantees), you can compose multi-chain applications without wrapping tokens endlessly. That reduces token proliferation, MEV surface area, and reconciliation complexity. Messaging reduces economic duplication; asset bridging (still necessary) remains but plays a smaller, more controlled role.

Example end-to-end flow

User locks 100 USDC on Chain A (on-chain custody contract emits event).

- Observers (three independent relayer nodes) see the event and submit Merkle proofs to a sequencer pool.

- Sequencer posts a batch to Chain B and a ‘pending mint’ is created with a 6-hour challenge window.

- Watchtowers read mempools and historic state; if any challenger proves fraud (discrepancy in header), batch is reverted and alarms trigger.

- After the window, mint finalizes. In parallel, operator insurance and slashing bond holders are staked to compensate failures.

This combines speed (batched posts) and integrity (challenge window + active watchers + slashing).

Developer checklist before integrating any bridge

- Who holds the private keys? Where are backups? (operational transparency)

- How is reorg-handling implemented? (confirmations vs finality proofs)

- Is there a dispute window? How long? What’s the UI impact?

- Are proofs independently verifiable on the destination chain? (light-client vs trusted-signature)

- What monitoring, alerting, and automated rollback mechanisms exist?

- What insurance, treasury backstops, or recovery bonding are in place?

If any of these answers are “unknown” or “manual,” treat the integration as high-risk.

For investors: what to look for in a bridge-native protocol

- Clear threat model documented publicly (who can do what)

- Economic defenses (slashing, bonded validators, multi-sig governance)

- Realistic UX around withdrawals (transparent challenge windows, withdraw simulations)

- Audit pedigree + continuous bug bounties (not one-time audits)

- On-chain proofs available for inspection (don’t trust opaque relayer logs)

Where interoperability is headed:-

- Native multi-deployments for major tokens (one canonical issuer, multi-chain native instances rather than wrapped variants).

- Seamless on-chain message standards (so contracts can call each other across chains with proven semantics).

- Modular chains with built-in IBC-like primitives (connectivity baked into execution layers).

- More insurance & on-chain forensics, the market buys certainty; expect capital to flow toward bridges that can show actuarial history.

Bottom line: A sober proposition for builders, operators, and investors

Bridges are the most consequential primitive in applied blockchain engineering. They are necessary, powerful, and perilous. Build like you mean it: model the attacker, harden the economics, decentralize observation, automate responses, and accept that some UX friction (challenge windows, staged withdrawals) is rational, not a bug.

Related Articles

- How to safely buy Bitcoin in 2025: a complete beginner’s roadmap with pro-level

- How real‑world assets (RWAs) on-chain are becoming crypto’s next trillion‑dollar narrative

- How to build a balanced crypto portfolio that works in both brutal bear phases and euphoric bull runs (2025 blueprint)

- Ultimate 2025 guide: how to protect your seed phrase from theft, fire, and family members

- Best Layer‑2 networks in 2025: Arbitrum, Optimism, zkSync and how they really compare